FANDOM Solo show at Contemporary art centre, Vilnius

2025

Curator: Virginija Januškevičiūtė

Click on the image or press <— / —>

In the solo exhibition Fandom, Anastasia Sosunova seeks to unlock the tensions, passions, and frustrations that arise between power and faith, encoded in rituals and concealed beneath the promises of DIY culture. She continues her series of works inspired by the spiritual teachings of the founder of Senukai hardware stores, which are disseminated through his books, radio programme, and the symbolic imagery associated with the company.

The exhibition’s title, Fandom, is a contemporary term referring to a community of fans devoted to a particular phenomenon. The artist views fan communities and their creative output as a compelling and highly relevant aspect of contemporary culture – one in which she also sees herself. Fans reinterpret – sometimes radically – narratives, signs, and characters created by others, constructing new plots and amplifying specific emotions. They heighten contrasts they perceive in the original works, sometimes even introducing entirely unexpected colours. Most importantly, fan creations are products of endless imitation and transformation, attracting vast audiences on virtual platforms such as YouTube and beyond – a phenomenon now studied by leading academics

The title of Sosunova’s new video, Xover, (third and final part of ‘Senukai trilogy’), is an abbreviation of crossover, a term referring to the merging of two or more fictional universes. As a format, fanfiction offers a space where vivid, conflicting, and ambiguous emotions can be fully expressed without concern for their alignment with ‘real’ reality – if such a thing exists at all.

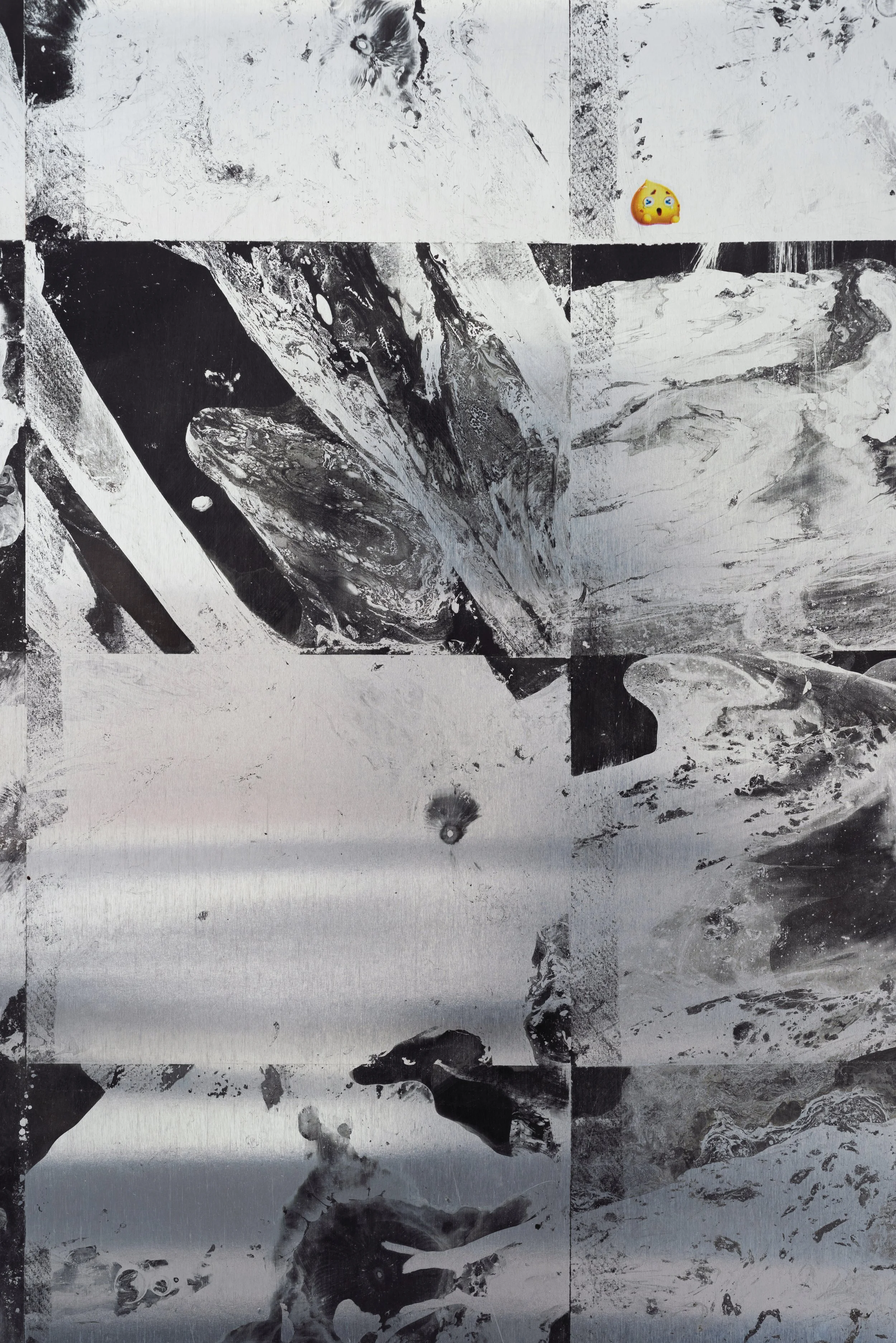

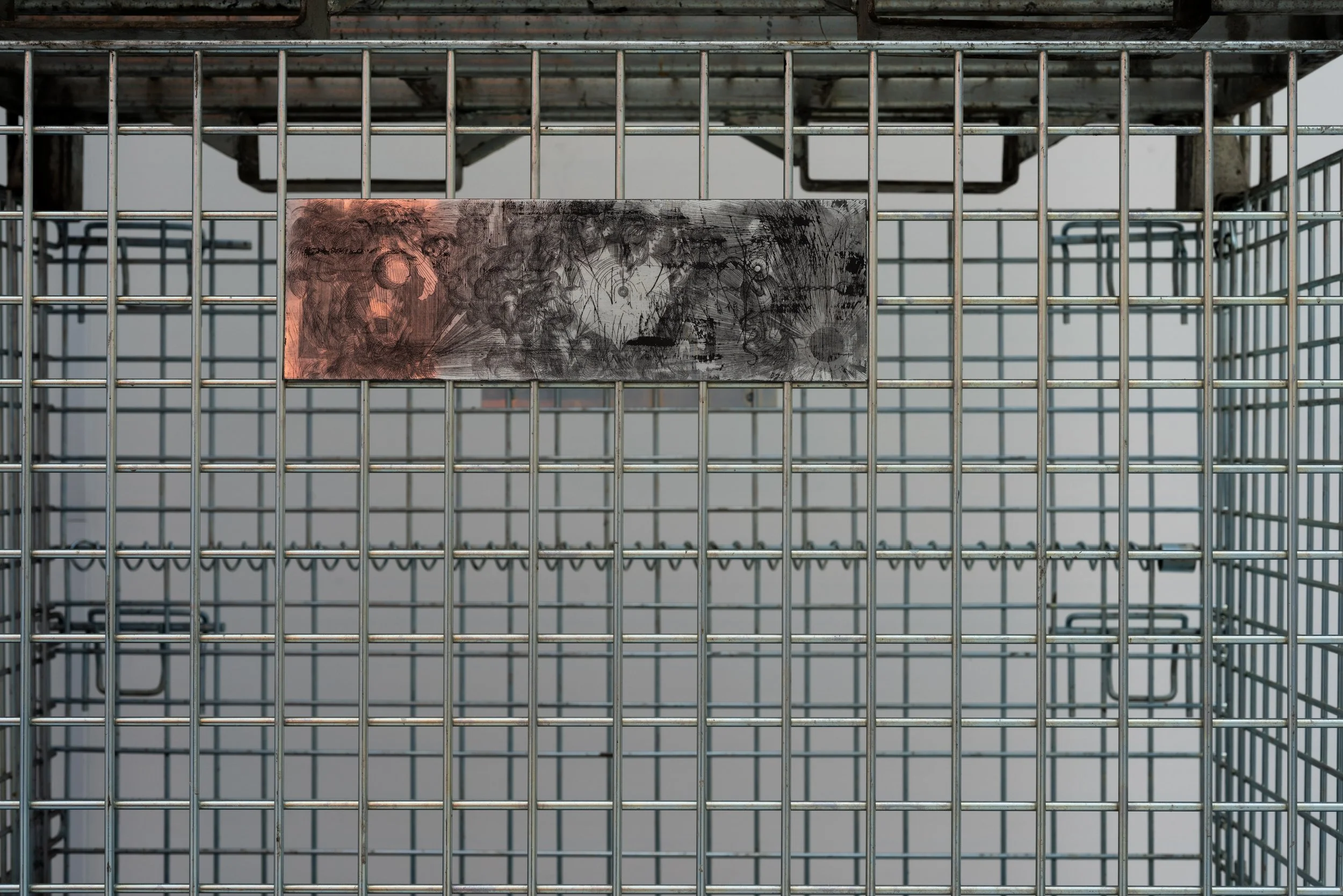

The video’s sound floods the entire exhibition space, integrating sculptures, graphic works, display equipment, and containers filled with obsolete video reproduction technology – abandoned by the images – into a visual collage. This discarded technology includes printers and scanners, security cameras, modems, cables, and screens, all awaiting transfer to recycling centers. Among them are objects, such as lawnmowers, that seem to have entered the frame by chance, spilling into the space.

Footage of bathers standing in the icy lake on the night of 18 January – when, in the Orthodox Christian tradition, water becomes sacred – gives way to shots of New Year’s fireworks. The artist is consistently drawn to places, events, and objects that encode the promise of faith, as well as the repetitions and chains of those events.

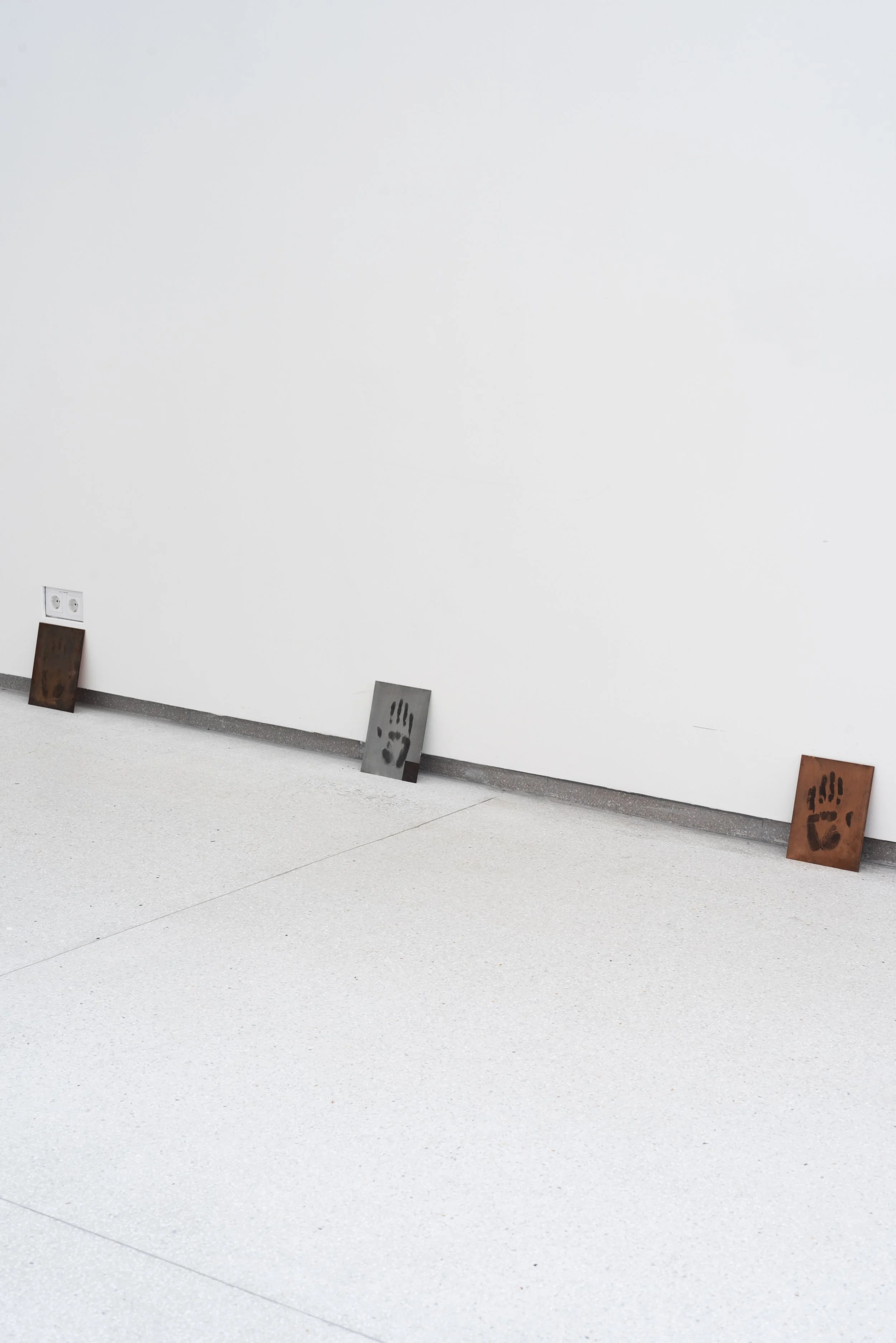

A special date, a testimony to a special touch. A relic frozen in time, marked by the imprint of a special person. A printing plate with a handprint rather than a print of the plate itself. The graphic matrix – the primal source of the original print – sends mirror images of itself into the world, the progenitor of contemporary images that multiply uncontrollably. The video screen as a printing press. A newspaper cliché from the last century, like a freeze-frame caught in the relentless stream of images flashing before our eyes at maddening speed – a remnant of the image-production process. A series of eights, marking infinity, in the emblem of Senukai. The endlessly recurring, ever-morphing forms of sea monsters.

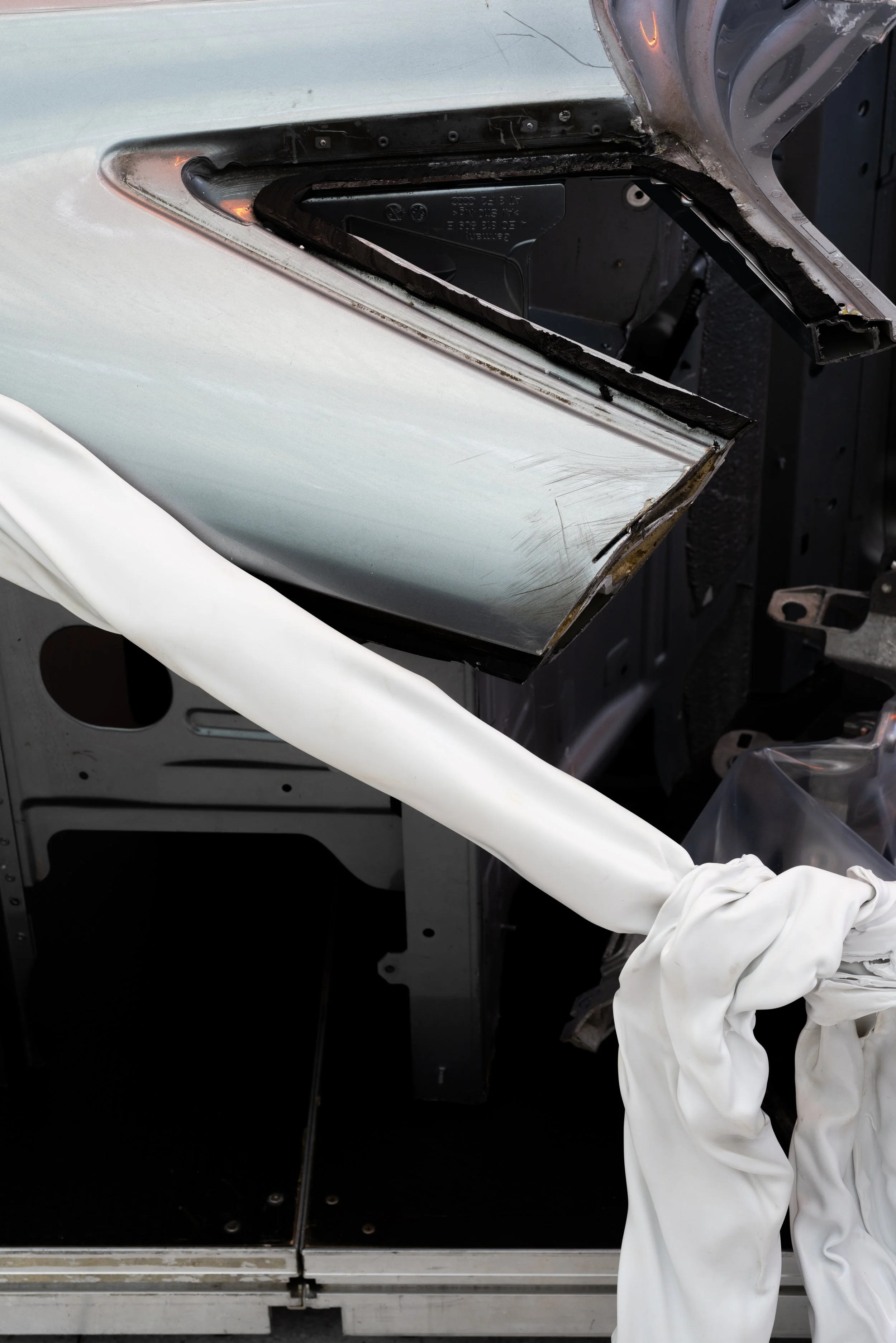

Lake water, collected that night, is mixed with water from Villa Unity in the Harmony Park SPA resort near the town of Prienai and incorporated into one of the sculptures – a lump of car wreckage and plastic, transformed into a reservoir of holy water.

In another sculpture, a salvo of the letter S – a recognisable element of the Senukai logo – becomes part of a depleted, improvised battery. Recharging it is both demanding and fleeting compared to conventional, mass-produced batteries with far greater power.

It is a crushing image of DIY ideology, highlighting the futility of trying to manage everything alone in modern society – or perhaps a premonition of a dystopian future, recalling the warnings of ancient prophets.

‘Villa Unity, Villa Synergy, Villa Abundance, Villa Strength, Villa Romovė, Villa Wisdom, Villa Prosperity, Yin and Yang helicopter landing’ – the film’s voice-over recites the names of the Harmony Park complex. It is no coincidence that the digital Harmony Park landscape created in collaboration with Jurgis Lietunovas, was generated using Unity software. The greatest drama in this work lies within the collision between imagined visions and experienced reality – the discrepancy between the prototypical image of a sacred place and the attempt to make it real. Harmony Park, Statybų duona (Lithuanian for ‘Construction Bread’, a hardware store), MEGA shopping mall – the relentless drive to create spaces that promise well-being carries a certain romantic allure, yet the rest of the world seems to be moving in a different direction.

Many of the theories of Athanasius Kircher, the famous 17th-century polymath, were later debunked – the status of the Man of Misconceptions stings. In one of Sosunova’s works, the eye of an ageing dog, slowly losing its sight, observes its own inevitable decay. An old newspaper cliché recounts the story of Destruction Park, a short-lived attraction that operated in an abandoned restaurant in the resort city of Palanga during the summer of 1999. There, visitors could vent their frustration and anger by destroying discarded household appliances. On his next adventure, the park’s founder chose to travel empty-handed – setting fire to his suitcases in the streets of Reykjavik on his way to the airport.

The era of Senukai defines the period since the artist’s birth, and much of the exhibition is imbued with an effort to bid it farewell – by any means necessary. In the tradition of iconoclasm, evil figures in religious imagery – such as Christ’s torturers in Crucifixion scenes – were often erased. Yet other parts of sacred images, like Christ’s feet, could also be worn away by countless kisses.

Exhibition text: Virginija Januškevičiūtė, photos: Jonas Balsevičius